I’ve been thinking about Planet Money’s recent podcasts about the automation of work, and especially about the episode on the Ziosk tablet making its way into restaurants. The Ziosk, in essence, is an extension of the point-of-service system right to your table – you can order appetizers, drink refills, and desserts, pay your bill, and there’s even a call button if you want to speak to your human waiter about something.

I’m conflicted about this particular device. The idea of going into TGIFridays and being greeted with a training session on how to use the e-menu struck me as a personal hell. I didn’t like the way that it made the waiter’s job sound a lot more stressful. The idea of a call button at a table – convenient as I have to admit it might be – also sounds just about a step away from snapping your fingers and the idea that “tip” means “To Ensure Promptitude.”

Don’t be that guy.

And I was congratulating myself on how I like talking to waiters, and finding out what’s good on the menu, and then the Planet Money folks said I could just pay my bill whenever I wanted. Now this is a service I’d appreciate. Nobody is getting any good at all out of me trying to catch the waiter’s eye, and them having to go run off a bill, and bring it back, and take my card, and run it, and bring back a receipt, and get a signature – yes, if I could be in charge of that wasted time, I could maybe live with things feeling a little more like an automat.

Ziosks improve restaurant profitability by turning over tables faster. They improve tips by having the tip default set at 20%. OK, these seem pretty obvious. And they increase average bills because people buy a lot more dessert from Ziosks than they do from waiters.

Mmmmm…. pie.

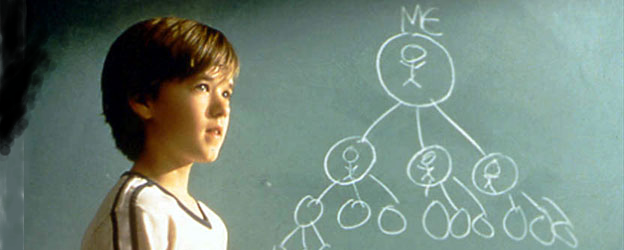

The story hypothesizes that it’s because the Ziosk isn’t judging you about your caloric intake… and that’s when I started wondering about education. We worry a lot about the students who don’t participate, or even worse, don’t come to office hours, because they’re afraid of being judged. We’ve devised all kinds of approaches to this problem – polling and peer instruction inside the classroom; office hours by email and chat and in coffee shops outside it. One might even argue that syllabi and rubrics and course websites should be designed to increase students’ information and decrease anxiety. Still the pressure exists – we didn’t reach all students, so we should do more. What does “more” even look like?

And what does employment in the academy look like when we get there? Is it an increasing pressure to be always-on? Is it an expanding dichotomy between Teachers and TAs and Advisors? Are courses more standardized for consistent experience? Or… here’s a crazy thought… can this be a discipline which allows us greater freedoms in the other areas? I’d argue that’s what’s currently happening with default answers like “read the syllabus” and “ask a librarian” – some questions get diverted to more efficient paths, letting the faculty member focus on different questions.

(This shoe fits the other foot, too, for those of us in academic support. How can we minimize the anxiety for faculty of asking for help with technology or teaching… or registration, or off-campus study advising, or library acquisitions, or any of the other million processes which are unfamiliar and scary? What do the systems look like which help faculty members describe their desires in ways which work?)

Of course, there’s a more constructionist interpretation of the dessert phenomenon too. Maybe people order more dessert from a tablet because they’re on autopilot. Maybe they order out of boredom more than anything else. Maybe it takes a human connection to get you to really sit with the question for a moment… Am I hungry? Am I satisfied? How do I feel? What do I want?

I know, that’s a grandiose interpretation of Death By Chocolate, but hell, it worked for Proust…

It’s easy to hide behind that constructionist belief, and say “what we do can’t be automated.” That’s not rising to the real challenge, though. Were we really present to each other? Did I really check in, or was “how are you?” just a different way to say “hi”? Did I give you want you want, or what I think you want, or did I take time to find out what you actually need?

The truth is, of course, we want both. We want a campus full of people who own their own learning, and have strong systems to help them do that. We also want to connect with those people, and extend their capacities and our own.

And the nice thing is, we can have that, if we take the time.

Image Sources

1) John Landis, The Blues Brothers. Found on BradVan316’s YouTube channel.

2) Berenice Abbot, “Automat, 977 Eighth Avenue, Manhattan.” From the New York Public Library’s Flickr channel. Listed as “No known copyright restrictions.”

3) la-fontaine, “Madeleine”. From http://pixabay.com/da/madeleine-cherry-tree-franske-kager-683743/ Licensed CC0 – Public domain.

Lani Guinier’s new book

Lani Guinier’s new book